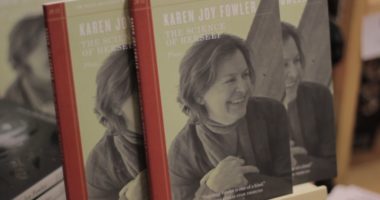

Interview with Karen Joy Fowler

Primates—their legal rights and their wellbeing—are in the news more than ever. Just this month, the USDA is considering ALDF’s petition to establish new standards of care for primates used in research, and the New York State Supreme Court is grappling with issues of legal personhood for chimpanzees. Meanwhile, ALDF is fighting the University of Wisconsin’s terror tests on baby monkeys. That’s just one of many reasons we were so excited to interview Karen Joy Fowler, author of the stunning novel We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, this month at Green Apple Books in San Francisco.

![]()

Although Karen was allowed in the rat lab as a child, she wasn’t allowed in the area where the monkeys were kept. One to a cage, the monkeys were separated; they could not touch each other. “As a small child it was clear to me that they were mad in every sense of the word. I’ll never know what was done to them but they are one of the reasons I wrote this book. I have spent my life haunted by those monkeys.”

Karen remembers Harry Harlow and his research. “He came to the lab and gave me a lemon drop. Later, when I read the details of what he was doing, it not only struck me as horrific but also–I don’t see what we’ve learned from that tragedy.” Exploiting animals in experiments is problematic, she continues. “I hope we can all agree that testing for cosmetics is an outrage. And the psychological testing I look at most in my book is not only outrageous in terms of the way the animals are treated but is also very suspect in terms of teaching us anything of value or anything we can be confident has any validity.”

Spoiler Alert: Reading this novel is a powerful experience too. It is a well-crafted story of sisterhood and brings light to the secretive world of animal testing. “The book is organized in such a way that it’s clear I intend you to be surprised about a third of the way through. My first person narrator justifies withholding this information because of the point she is trying to make – that the sister she has been telling you about is not a human child but a chimpanzee. “It’s still the story of a family, of a sister, of a lost sister.”

Writing this novel had an impact upon the author as well. “The argument I initially wished to make was that because primates are so human-like, they deserve to be treated in a more humane and human-like way. As I was writing the book, my feelings changed. I looked at more studies of animal cognition in different species. I asked myself why being human-like was the thing that mattered to me. Why did that mean that an animal deserved to be treated well? “

Premiere primatologist Frans De Waal, author of The Bonobo and the Atheist, says empathy is a primate behavior we come by naturally. “We don’t need a church, or our parents, or society telling us how to move morally through the world. With empathy as our guide, we know how we ought to behave,” Karen explains. “But we extend empathy only to those we think of like ourselves. Anyone we think of as ‘other’ we have an antipathy with, that is part of our primate nature.” We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves is a literary way of extending beyond that orbit of empathy to care about other species.

“As the title of my book suggests, I have come to think of one of the primary roles of literature and art being the extension of our sense of who is like us and therefore the extension of our empathy. As we read books we can think about what it would be like to be other people, to live in other cultures. I would like to go even further and have our empathy extend beyond our species. I would like a world in which we recognize that we are all completely beside ourselves.”

Chimpanzees are the animals we are closest to, genetically and in terms of recognizably human-like intelligence. But, “in the fast-moving field of animal cognition, we are learning that we have underestimated the creatures we share the planet with at every juncture and in every possible way. So in writing this book I started with a very human lens and have tried to grow beyond that.”

The painting for the cover of the book is by Congo, who lived most of his short life in the London Zoo, Karen Joy Fowler notes. “He left quite an astonishing body of work behind. I think it’s really beautiful and I hope other people think so too.”

Focus Area

Related

-

CDC Seeks to End Program Using Monkeys in Research

The Animal Legal Defense Fund continues to advocate for animals suffering in research labsDecember 8, 2025 News -

Washington Governor Signs Animal Protection Bills into Law

The four laws will offer better protections for companion animals and keep wild animals from being exploited for entertainment in the stateMay 16, 2025 News -

Captive Primate Safety Act Reintroduced in the U.S. House to Protect Nonhuman Primates

Bill will prohibit the type of private possession of nonhuman primates portrayed in the HBO Max docuseries “Chimp Crazy”May 6, 2025 Press Release